REIMAGINING MISSIONS: PARADIGMS PATHS & PARTNERSHIPS

[20 Minute Read]

Dear fellow participants in God’s mission,

Grace and peace to you in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ.

Facing momentous change, missional leaders and practitioners face daunting complexities and remarkable new opportunities. Long-held patterns of sending and receiving are giving way to vibrant, interdependent, collaborative efforts spanning languages, cultures, contexts and continents. Instead of relying solely on inherited structures or leadership models of a bygone era, today’s endeavours can draw upon a tapestry of wisdom, gifting, and collaborative creativity emerging from every part of the global church.

Paradigms can shift dramatically when old ways of thinking no longer address new realities.

Into this dynamic and evolving space, David Bosch, in his text “Transforming Mission“, brought to our attention the concept of paradigms when he categorized the 2,000-year history of the church in mission into six main epochs. A paradigm is an underlying framework or map that shapes how a community interprets and engages with reality. Paradigms can shift dramatically when old ways of thinking no longer address new realities. Such moments can feel unsettling. However, they can also become “an opportunity for course correction” with fresh insights and renewed purpose.

A Paradigm Shift Case Study

By examining how paradigms form, shift, and mature, we can navigate uncertainty and influence the future shape of the missional purpose of our ministries. A case study based on “A Missional Leadership History” follows.[1] By tracing the winding journey of one mission agency as it transforms from a Western-based operation into a global movement, we can better discern how tomorrow’s missional leaders might navigate new terrains with humility, courage, and Spirit-led innovation.

1) Founding (1942-1965)

The Wycliffe Global Alliance (WGA) traces its roots back to the early 1940s with the founding of Wycliffe Bible Translators (WBT) by W. Cameron Townsend and William Nyman, both from the US. Townsend, who had already formed the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL) in 1934, embodied faith in God’s provision and a pragmatic, ‘whatever it takes’ leadership style. This approach stimulated the development of new WBT offices in the Western world.

As George Cowan, WBT President Emeritus, later summarized, the fledgling movement faced “untrained, weak, raw recruits; opposition from church and mission leaders; extreme poverty amid the Great Depression; lack of training materials; and opposition from various ideologies.” Yet through it all, Cowan noted, “God’s miracles [were] abounding,” evidence that the Lord’s guiding hand brought Townsend and WBT through these formative years.[2]

Two leadership approaches affected this era: Traits-based (the Great Man theory) and Charismatic. Western men held most leadership roles. Trait-based theory assumed some individuals were born with “drive, vigour, risk-taking, initiative, self-confidence and influence.”[3] Similarly, Charismatic leadership emphasized a leader’s “presence” and ability to “infuse organizations with meaning.” [4]

2) Expanding (1966–1980)

A ‘West to the rest’ mindset dominated missions during this era, describing how the Gospel message was envisioned to reach the entire world. WBT relied on Western resources of personnel, funding, and academic expertise. The organizational structures were called ‘Divisions,’ meaning a branch of the primary US operations. The system, by default, kept Westerners in charge because of their availability.

WBT’s leadership reflected three theories: Behavioural, Situational, and Path-goal. Behavioural leadership focused on tasks and relationships. Situational leadership required adapting styles to follower needs; however, WBT’s personnel resisted overly directive approaches. Path-goal aimed to motivate followers; rather than financial incentives, spiritual motivation and a Protestant work ethic motivated WBT’s leaders.

3) Creating (1981–1990)

Wycliffe Bible Translators International (WBTI) emerged, adding ‘International’ to the name but not fully grasping how to integrate newly established local Bible translation organizations. Throughout the 1980s, WBTI’s role as a catalyst for a global Bible translation movement took shape. Divisions formed, and more Christians across Europe, Asia, the Pacific, Africa, and the Americas joined in. European organizations sought greater autonomy, prompting WBTI to transition into an organization of autonomous entities.

During this era, WBTI’s leadership reflected three approaches: Transformational, Transactional, and Laissez-faire. Transformational leadership emphasized vision, strategy, trust-building, and developing followers beyond their expected contributions. Transactional leadership offered rewards for compliance, while Laissez-faire allowed leaders to withdraw enough to empower others to act. Overall, WBTI’s leaders guided a diverse network with influence and motivation rather than strict authority.

4) Maturing (1991–2000)

WBTI saw its Divisions become independent nonprofits with a name change to ‘Wycliffe Organizations’ (WOs) that raised funds and engaged prayer support and personnel for SIL International. Meanwhile, the National Bible Translation Organizations became ‘Wycliffe Affiliates’ and managed Bible translation programs in their own countries. The WOs and Affiliates came from the Americas, Europe, Asia, the Pacific, and Africa. As WBTI grew more multicultural, its board and leadership adapted structures to govern effectively. Near the decade’s end, WBTI and SIL adopted ‘Vision 2025’, aiming to begin a Bible translation in every needed language by 2025—a response to how long it was taking to get work started.

In this decade, WBT’s cultural value of autonomy persisted. Meanwhile, Servant leadership theory gained momentum. Robert K. Greenleaf’s approach, influenced by Judeo-Christian roots, fused ‘servant’ and ‘leader’—opposite roles—to stress trust, moral authority, and empowering followers.[5] WBTI’s servant-oriented mission aligned naturally with servant leadership’s principles.

5) Moving (2001–2010)

During this decade, WBTI adapted to global changes, focusing on engaging with the church’s growth in the Majority World. In 2008, a restructuring of the joint International Administration with SIL resulted in WBTI having its own leadership team that supported 48 Wycliffe Member and over 50 Partner Organizations. In 2003, the WBTI Board committed to engaging the Majority World church by nurturing an environment where inter-organizational relationships could thrive.

During this era, leadership theories diversified, distinguishing leadership from management,[6] emphasizing change over complexity, and highlighting moral influence over positional authority. A good example was Level 5 leadership, where a leader’s ambition concerns their organization’s mission rather than personal gain.[7] Shepherd leadership compassionately uses diverse skills and techniques according to the necessities of the context.[8] Complexity leadership theory embraced uncertainty, distributed intelligence, and adaptive, collaborative learning.[9] These perspectives influenced WBTI’s evolving context. Recognizing that no single leader held all solutions, WBTI increasingly valued shared learning, adaptability, and ethical integrity.

6) Birthing (2011-2015)

By 2011, WBTI changed its name to the Wycliffe Global Alliance (WGA). This was more than a name change; however, it signified moving from a hierarchal structure to a community of organizations, from centralized control to multiple levels of collaboration.

Vision 2025 had highlighted the need for meaningful partnerships with the global church, and WGA emerged as an ‘organization of organizations,’ no longer just a resource provider to SIL International. While the structural simplification reduced complexity in one sense, WGA now served a culturally diverse, worldwide network of varying sizes and purposes. This demanded fresh leadership approaches to guide the growing global community.

During this era, the WGA’s leadership values emphasized dependence on the Lord, greater cultural sensitivity, and commitment to community-building. These values integrated biblical and missiological principles, engaging thoughtfully with complex, cross-cultural issues. Leaders were encouraged to avoid quick fixes, invest in people, cultivate collaborative relationships and creative thinking, understand cultural norms, balance adaptability without abandoning core values, prevent distrust, and courageously navigate change.

7) Flourishing (2016–2020)

Ownership of WGA’s mission was no longer centred in the West but expanded worldwide. Instead of depending on a single region, influence flowed from culturally diverse communities, fostering mutual learning.

WGA’s leadership approach drew on emerging models. Steward leadership focused on God as the owner and addressed accountability, authority, and resource management for greater effectiveness.[10] Humble leadership encouraged innovative solutions by building relationships through mutual learning, listening, and leveraging collective wisdom.[11] Missional leadership was transformative through the Holy Spirit’s guidance to participate in God’s mission.[12]

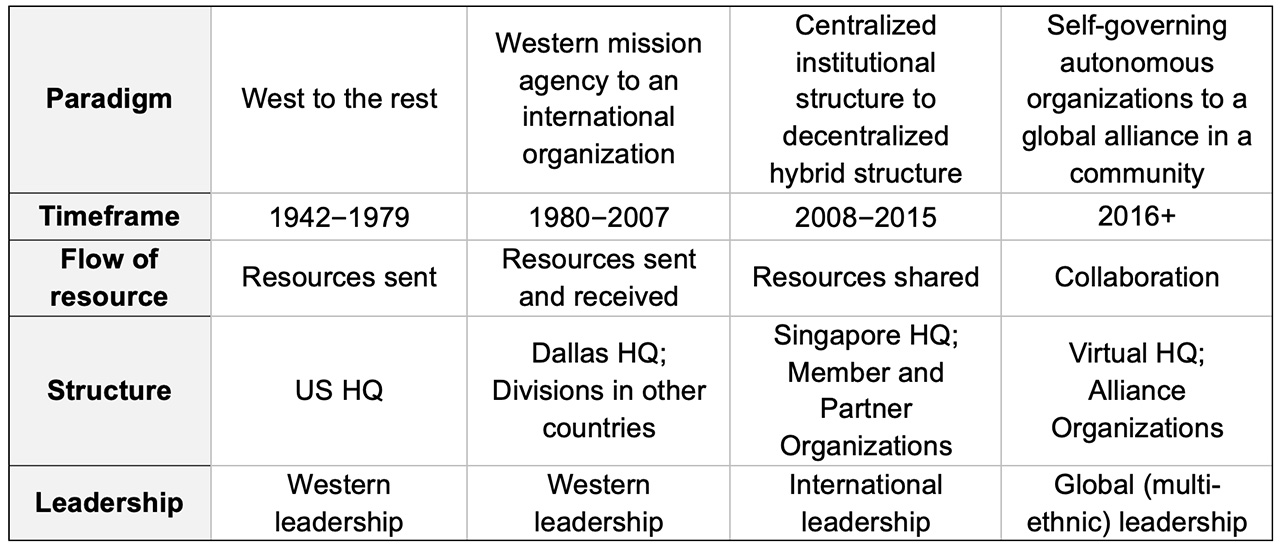

Learning From The Case Study

This case study offers insights into leadership and organizational transformation in a global missional context. WGA’s journey from a US-based mission agency to a global movement demonstrates how paradigm shifts reshape mission structures, leadership practices, and community engagement. These shifts are summarized in this table:[14]

What is not shown but has impacted WGA’s journey is a process that started in 2006. This was its first missiological consultation. Since then, over 30 consultations, each with anywhere from ten to hundreds of participants from around the world, have been held to discuss topics ranging from ecclesiology to funding to community.

Stephen Coertze, who oversaw most of these consultations, outlines the critical elements used in this consultative process as: “(1) Understand the biblical message and its most significant themes; (2) Develop an awareness of how God is at work, both in history and in the world today; (3) Understand people in their environments; (4) Cooperate with the Holy Spirit; (5) Collaborate with others in community; (6) Understand the interdisciplinary nature of missiology.”[15]

While it is difficult to quantify the collective impact these consultations had on WGA’s journey, there is no question as WGA leader Susan Van Wynen writes, “of the value, richness, and depth of consultation conversations and discoveries” along with “the contexts in which the consultations were held, the polyphonic contributions of so many pivotal voices, and the prayers and processes of creating community.”[16]

Effective leadership transformed the insights from these consultations into tangible steps that shaped WGA’s future. The consultations left lasting markers—memories, lessons, and guiding milestones—enabling WGA to chart new territory with both confidence and humility, continually recognizing God’s guiding hand along the way.

Reimagining missions through shifting paradigms is not a one-time task; it is an ongoing pilgrimage shaped by the Spirit and guided by the communities we serve.

Reimagining missions through shifting paradigms is not a one-time task; it is an ongoing pilgrimage shaped by the Spirit and guided by the communities we serve. As this case study reveals, the Wycliffe Global Alliance did not merely alter its structures or policies; it learned to listen across diverse contexts, foster trust, and extend authentic reciprocity in decision-making and resource-sharing.

For today’s missional practitioners and thinkers, this journey provides a compelling invitation: Embrace uncertainty as fertile ground for growth, welcome the wisdom of God’s people from across the globe, and find the courage to chart unexplored paths. In doing so, we can cultivate a resilient, humble, and collaborative witness that emboldens the global church to meet the future with hope, ready to embody God’s reconciling love in fresh and transformative ways.

References and sources used for this essay:

-

Kirk Franklin, and Paul Bendor-Samuel, The Mission Matrix: Mission Theologies for Diverse Mission Landscapes (Oxford, UK: Regnum Books, 2024), 22.

-

Kirk Franklin, and Susan Van Wynen, A Missional Leadership History: The Journey of Wycliffe Bible Translators to the Wycliffe Global Alliance (Oxford: Regnum Books International, 2022), 20, 49, 80, 112, 55, 220, 67.

-

George Cowan, “Presentation to WBTI Board,” May 2003.

-

Peter Northouse, Leadership: Theory and Practice, 8th ed. (London: SAGE Publications, 2019), 22.

-

James MacGregor Burns, Transforming Leadership (New York: Gove Press, 2003), 27.

-

Robert K. Greenleaf, Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Grateness (Ramsey: Paulist Press, 1977), 7.

-

C. Otto Scharmer, Theory U: Leading from the Future as It Emerges (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publications, 2009).

-

James Collins, Good to Great, vol. Random House Business Books (London, UK, 2001).

-

Timothy Laniak, Shepherds after My Own Heart: Pastoral Traditions and Leadership in the Bible (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2006).

-

Mary Uhl-Bien, Russ Marion, and Bill McKelvey, “Complexity Leadership Theory: Shifting Leadership from the Industrial Age to the Knowledge Era,” The Leadership Quarterly 18, no. 4 (2007).

-

Kent Wilson, Steward Leadership in the Nonprofit Organization (Downers Grove: IVP, 2016).

-

Edgar Schein, and Peter Schein, Humble Leadership: The Power of Relationships, Openness, and Trust (Oakland: Berrett-Koehler, 2018).

-

Nelus Niemandt, Missional Leadership (Cape Town: AOSIS, 2019), 73.

-

Franklin, and Van Wynen, 309.

-

Franklin, and Van Wynen, 382.

-

Franklin, and Van Wynen, 448.

Pray

- For an increasing awareness of the global context changes that are affecting the efficacy of missions organisational and missionary practices in cross-/trans-/inter-cultural settings. Understanding our context influences paradigm awareness.

- For wisdom for missions organisation leaders (governance and operational) as they consider paradigm shifts and associated leadership models necessary to help their organisations find better ways to be fit for purpose into the future.

- For increased sensitivity to the cultural variety of relationships international organisations multiply as they grow, and a willingness to yield to cooperative internationalisation rather than protecting a single culture’s dominance over the organisations policies, practices, ethos, values, and culture.

- That the Holy Spirit will indeed continue to lead international missions to innovate for more effective participation in the purposes of God around the world.